When Quoting Variables Backfires: A Deep Dive into Bash Expansion

While we often hear the advice "always quote your variables in Bash", there are specific scenarios where using quotes can lead to unexpected behavior. This post explores when quotes around variables can be problematic and explains the underlying Bash expansion process by diving into its source code.

Background: An issue caused by quotes

While migrating a continuous delivery (CD) process to Tencent Cloud, I initially used coscli, Tencent's official CLI tool. However, I encountered a frustrating issue: if the coscli cp command fails, it doesn't return a non-zero exit code, causing GitHub Actions workflows to hang until the six-hour timeout. To support other S3-compatible cloud storage providers and avoid vendor lock-in, I switched to rclone. In my previous post, Always Use Braces Around Variables in Bash/Zsh, I shared lessons from implementing the CD process with rclone. This post dives into a Bash command processing issue I encountered while using coscli.

Troubleshooting this Bash expansion issue gave me deeper insight into what happens after you enter commands in a terminal. In this post, I will explain how double quotes around variables, such as "$ARGS", can sometimes cause unexpected issues and what actually happens during Bash's expansion process.

My journey began with a script that successfully connected to a Tencent Cloud storage bucket on my local machine. However, when I migrated this to a GitHub Actions workflow and stored the arguments in a variable (COSCLI_ARGS) for easier maintenance, it unexpectedly failed.

- Local Bash script

- GitHub Actions workflow

- Error output

#!/bin/sh

set -x

# Download and set up coscli

curl -fsSL https://cosbrowser.cloud.tencent.com/software/coscli/coscli-linux-amd64 >coscli && chmod +x ./coscli

# Define environment variables

TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_ID="***"

TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_KEY="***"

TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID="***"

# List contents of the bucket

./coscli ls \

--endpoint "cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com" \

--secret-id "${TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_ID}" \

--secret-key "${TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_KEY}" \

--init-skip=true \

"cos://${TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID}/test"

name: Debug COS Bucket Access

on:

workflow_dispatch:

jobs:

run:

name: Debug COS Bucket Access

runs-on: ubuntu-22.04

env:

COSCLI_ARGS: >

--endpoint "cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com"

--secret-id "${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_ID }}"

--secret-key "${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_KEY }}"

--init-skip=true

TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID: ${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID }}

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Install coscli

run: curl -fsSL https://cosbrowser.cloud.tencent.com/software/coscli/coscli-linux-amd64 >coscli && chmod +x ./coscli

- name: List bucket contents

run: ./coscli ls $COSCLI_ARGS "cos://$TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID/test/"

Run ./coscli ls $COSCLI_ARGS "cos://$TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID/test/"

./coscli ls $COSCLI_ARGS "cos://$TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID/test/"

shell: /usr/bin/bash -e {0}

env:

COSCLI_ARGS: --endpoint "cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com" --secret-id "***" --secret-key "***" --init-skip=true

TENCENTCLOUD_BUCKET_ID: ***

ERRO invalid bucket format, please check your cos.BaseURL

To debug, I added set -x to see the exact command being executed:

+ ./coscli ls --endpoint '"cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com"' --secret-id '"***"' --secret-key '"***"' --init-skip=true cos://***/test/

ERRO invalid bucket format, please check your cos.BaseURL

When I compared this with how the command runs successfully on my local machine, I noticed a critical difference:

+ ./coscli ls --endpoint '"cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com"' --secret-id '"***"' --secret-key '"***"' --init-skip=true cos://***/test/

- ./coscli ls --endpoint cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com --secret-id '***' --secret-key '***' --init-skip=true 'cos://***/test'

The issue was that the --endpoint value in the GitHub Actions workflow had extra quotes ('"cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com"'), which made it invalid for coscli.

The solution was straightforward: I removed the quotes around the arguments in the COSCLI_ARGS variable.

- Before

- After

env:

COSCLI_ARGS: >

--endpoint "cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com"

--secret-id "${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_ID }}"

--secret-key "${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_KEY }}"

--init-skip=true

env:

COSCLI_ARGS: >

--endpoint cos.ap-beijing.myqcloud.com

--secret-id ${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_ID }}

--secret-key ${{ secrets.TENCENTCLOUD_SECRET_KEY }}

--init-skip=true

Experimentation: The actual arguments received

Although removing the quotes resolved the issue, I wanted to dig deeper to understand the root cause. Specifically, I aimed to clarify when to quote variables and when not to. To investigate, I wrote a script, myecho, to display the actual arguments received by a command:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

print("\n".join(f"argv[{idx}]=|{arg}|"for idx, arg in enumerate(sys.argv)))

This script prints each argument passed to it, along with its position in the argument list. I then created several test cases to explore how Bash handles variable expansion and quoting.

- Unquoted variable

- Quoted variable

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho $ARGS

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg|

# argv[2]=|"1|

# argv[3]=|2|

# argv[4]=|3"|

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho "$ARGS"

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg "1 2 3"|

I expected the command to receive two arguments: --arg and "1 2 3". When I ran ./myecho "$ARGS", the entire string --arg "1 2 3" was passed as a single argument. However, running ./myecho $ARGS produced the following output:

argv[0]=|./myecho|

argv[1]=|--arg|

argv[2]=|"1|

argv[3]=|2|

argv[4]=|3"|

This was surprising: Bash split the argument string at each space, even those within the quoted substring, treating them as delimiters rather than preserving the substring's integrity.

Investigation: The order of Bash expansion

- Expansion is performed on the command line after it has been split into words.

- The order of expansions is: brace expansion; tilde expansion, parameter and variable expansion, arithmetic expansion, and command substitution (done in a left-to-right fashion); word splitting; and pathname expansion.

- After these expansions are performed, quote characters present in the original word are removed unless they have been quoted themselves (quote removal).

This section focuses on parameter expansion and word splitting, as they are directly relevant to the test cases.

Greg's wiki on Arguments helped me understand these concepts. I will follow the Bash processing order outlined in this document (quoting/escaping -> parameter expansion -> word splitting) to explain them.

-

Quoting/escaping: marks characters as literal rather than syntactical, protecting them from being interpreted as special characters. For example:

# Print the content of a file with spaces in its name:

cat "This is a file.md" -

Parameter expansion: extracts data from a variable and inserts it into the command. For example, the variable

$FILENAMEis replaced by its value,test.md:FILENAME="test.md"

cat $FILENAME

# After parameter expansion: cat test.mdtipThe value of

FILENAMEistest.md, not"test.md", because the variable's value undergoes expansion and quote removal before being stored. -

Word splitting: after expansion, Bash splits words based on the IFS (Internal Field Separator). By default, IFS includes spaces, tabs, and newlines.

./myecho "This is a file.md"

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|This is a file.md|

./myecho This is a file.md

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|This|

# argv[2]=|is|

# argv[3]=|a|

# argv[4]=|file.md|

Let's apply these concepts to the test cases.

- Unquoted variable

- Quoted variable

For the unquoted variable case:

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho $ARGS

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg|

# argv[2]=|"1|

# argv[3]=|2|

# argv[4]=|3"|

- Quoting: not applicable.

- Parameter expansion:

$ARGSexpands to--arg "1 2 3". - Word splitting: the spaces in

--arg "1 2 3"are treated as syntactical, not literals. As a result, the string is split into--arg,"1,2, and3".

For the quoted variable case:

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho "$ARGS"

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg "1 2 3"|

- Quoting:

"$ARGS"ensures that all characters in$ARGSare treated as literals. - Parameter expansion:

"$ARGS"expands to"--arg "1 2 3"". - Word splitting: not applicable because the spaces in

"--arg "1 2 3""are treated as literals.

From Greg's wiki, I also learned that for my use case, a better approach is to store arguments in an array instead of a string. :)

- Before (using a string)

- After (using an array)

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho $ARGS

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg|

# argv[2]=|"1|

# argv[3]=|2|

# argv[4]=|3"|

ARGS=(--arg "1 2 3")

./myecho "${ARGS[@]}"

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg|

# argv[2]=|1 2 3|

Revelation: Digging into the rabbit hole

Curious about how these two cases differ during runtime execution, I decided to dive deeper by cloning Bash's source code and debugging both scenarios step by step. The execution path is intricate, so I will focus on the key steps and skip some of the finer details in the following explanation.

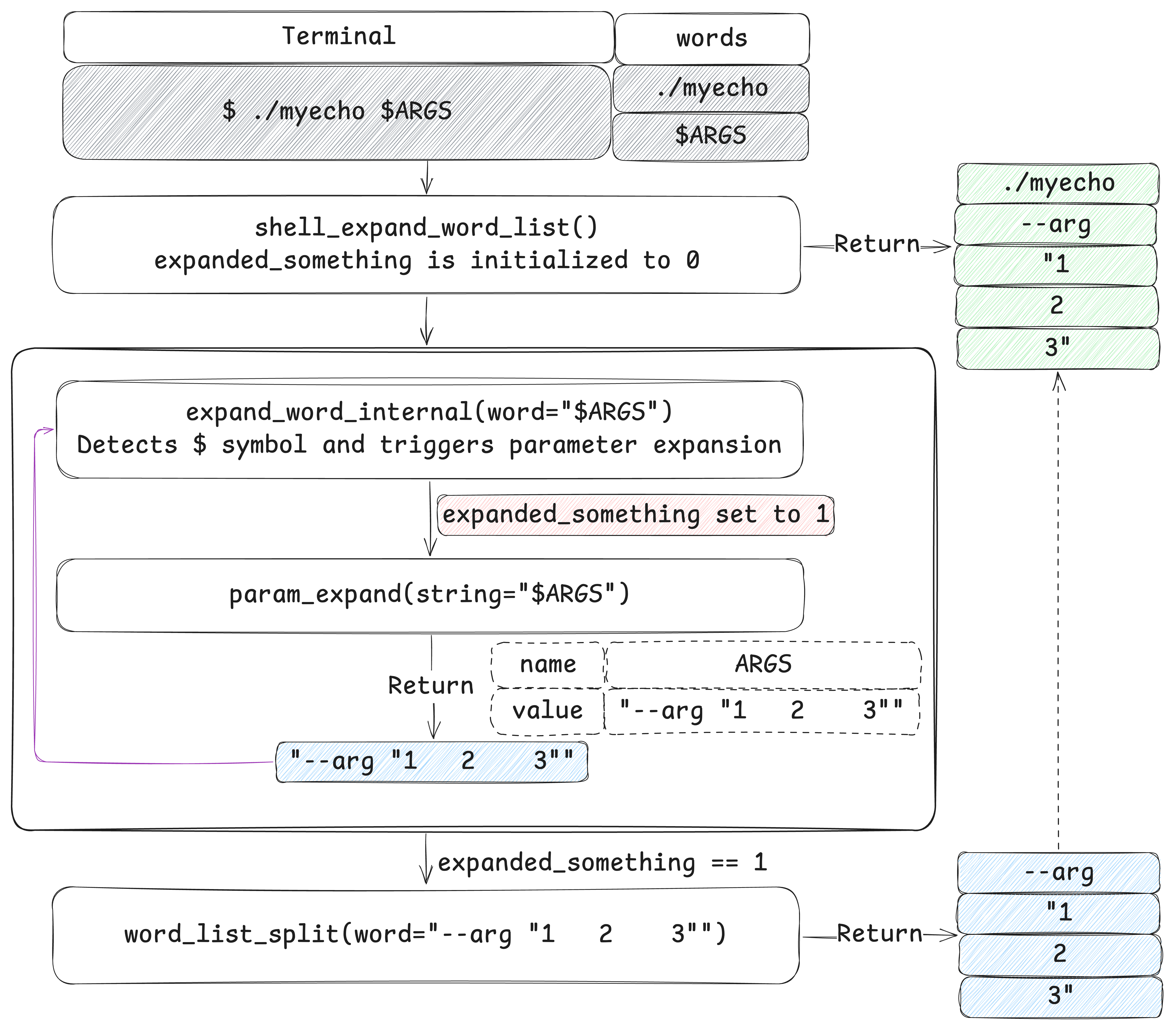

Case 1: Unquoted variable

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho $ARGS

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg|

# argv[2]=|"1|

# argv[3]=|2|

# argv[4]=|3"|

The following is a step-by-step breakdown of what happens:

-

Lexical analysis

Bash identifies

./myechoand$ARGSas two separate words after lexical analysis. The simplified data structure ofcurrent_commandlooks like this:current_command: {

type: "cm_simple",

value: {

Simple: {

words: {

word: "./myecho",

next: "$ARGS"

}

}

# Other command types, such as For, Case, and While, are omitted.

}

} -

Command execution

Bash calls

execute_simple_command()withcurrent_command.value.Simpleas input. Inside this function,expand_word_list_internal()handles the expansion of each word. The first word,./myecho, is processed directly. Now, let's focus on how$ARGSis expanded.

-

Word expansion

expand_word_list_internal()callsshell_expand_word_list(), initializingexpanded_somethingto0. Then,expand_word_internal()is called recursively:expand_word_internal()processesword="$ARGS"character by character. The first character$triggers parameter expansion. Then,expanded_somethingis set to1, andparam_expand()is called.param_expand()processesstring="$ARGS"withexpanded_something=1, identifies the variableARGS, and returns its value:--arg "1 2 3".expand_word_internal(word="$ARGS")returns--arg "1 2 3", withexpanded_somethingnow set to1.

-

Word splitting

Since

expanded_somethingis1,word_list_split()splitsword="--arg "1 2 3""into--arg,"1,2, and3". -

Result of word expansion

shell_expand_word_list()returns the following word expansion result for$ARGS:new_list: {

word: "--arg",

next: {

word: ""1",

next: {

word: "2",

next: {

word: "3"",

next: NULL

}

}

}

} -

Result of command execution

expand_word_list_internal()returns the complete word list for./myechoand$ARGS, which Bash uses to construct anexecve()system call:words: {

word: "./myecho",

next: {

word: "--arg",

next: {

word: ""1",

next: {

word: "2",

next: {

word: "3"",

next: NULL

}

}

}

}

}

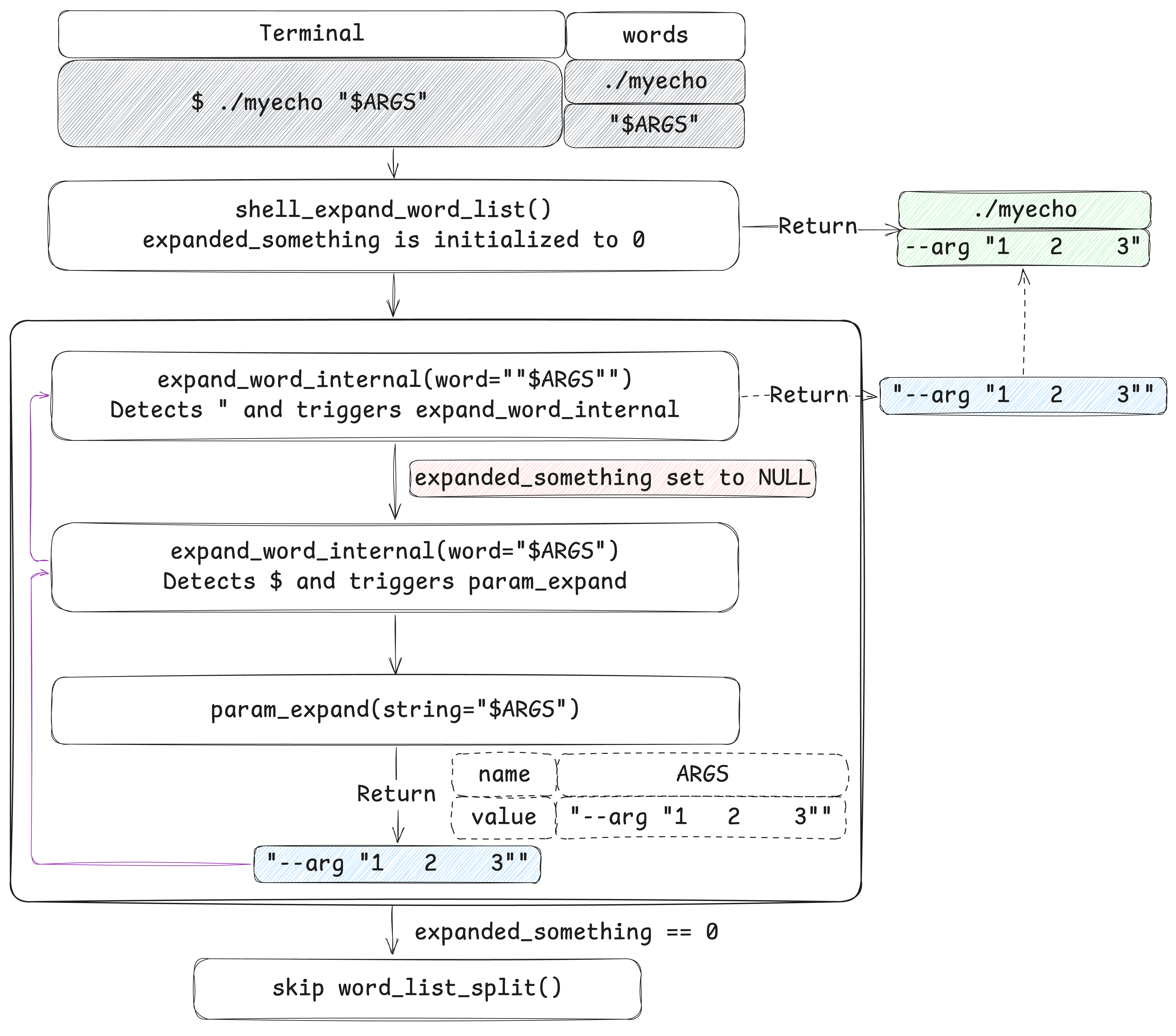

Case 2: Quoted variable

ARGS='--arg "1 2 3"'

./myecho "$ARGS"

# argv[0]=|./myecho|

# argv[1]=|--arg "1 2 3"|

The following is a step-by-step breakdown of what happens:

-

Lexical analysis

Bash identifies

./myechoand"$ARGS"as two separate words after lexical analysis. The simplified data structure ofcurrent_commandlooks like this:current_command: {

type: "cm_simple",

value: {

Simple: {

words: {

word: "./myecho",

next: ""$ARGS""

}

}

# Other command types, such as For, Case, and While, are omitted.

}

} -

Command execution

Bash calls

execute_simple_command()withcurrent_command.value.Simpleas input. Inside this function,expand_word_list_internal()handles the expansion of each word. The first word,./myecho, is processed directly. Now, let's focus on how"$ARGS"is expanded:

-

Word expansion

expand_word_list_internal()callsshell_expand_word_list(), initializingexpanded_somethingto0. Then,expand_word_internal()is called recursively:expand_word_internal()processesword=""$ARGS""character by character. The first character is", so Bash callsstring_extract_double_quoted()to extract the content, which returns$ARGS.expand_word_internal()processesword="$ARGS"withexpanded_something=NULL. This indicates that the initial value ofexpanded_somethingremains unchanged during this recursion. The first character$triggers parameter expansion.param_expand()processesstring="$ARGS"withexpanded_something=NULL, identifies the variableARGS, and returns its value:--arg "1 2 3".expand_word_internal(word="$ARGS")returns--arg "1 2 3".- The outer

expand_word_internal(word=""$ARGS"")returns--arg "1 2 3", andexpanded_somethingremains0.

-

Word splitting

Since

expanded_somethingis0,word_list_split()is not performed onword="--arg "1 2 3"". -

Result of word expansion

shell_expand_word_list()returns the following word expansion result for"$ARGS":new_list: {

word: "--arg "1 2 3"",

next: NULL

} -

Result of command execution

expand_word_list_internal()returns the complete word list for./myechoand"$ARGS", which Bash uses to construct anexecve()system call:words: {

word: "./myecho",

next: {

word: "--arg "1 2 3"",

next: NULL

}

}

My Bash journey: From copy-pasting to puzzle pieces

Fifty days ago, I fell down the rabbit hole of Bash expansion. What started as a simple quote-related issue led me to repeatedly read Bash documentation and Greg's wiki, and eventually the source code itself. Diving into Bash's source code became one of the boldest moves I made this year. Before this deep dive, my understanding of Bash expansion came from scattered documentation and observed behaviors. It wasn't until I studied the actual implementation that I truly grasped how it works, particularly regarding parameter expansion and word splitting.

Actually, two years ago, when writing Bash scripts, I'd mechanically wrap variables in curly braces and quotes, or use IFS= in while loops without understanding why. I followed these "best practices" simply because ShellCheck told me or Stack Overflow answers suggested them. But after spending a few nights figuring out Bash's expansion, I finally get why those practices exist.

This mirrors my journey with Git and Docker. Early on, I relied on memorization and copy-pasting. But that changed with deeper learning about their internal mechanisms. On the surface, the way I use Git and Docker now might look the same as two years ago. But now, I know what I'm doing, why it works, and how to troubleshoot issues. I can handle custom needs, critically review LLM-generated commands, and adapt to unexpected situations.

An interesting story is that after reading Docker build cache, I decided to optimize a Dockerfile I wrote years ago. To my surprise, I had already implemented multi-stage builds—even though I didn't know what multi-stage builds were at the time. (I linked to the GitHub version of the document because the official one was later restructured, and I prefer this version's organization and step-by-step optimization guidance.)

Some might ask, "Why bother researching things you can use directly without understanding them? You'll forget the details anyway." They're right - specific implementation details will fade. But the experience of investigation, the process of uncovering how things work, that feeling will remain. More importantly, I have a new understanding of what happens when I type a command in the terminal. If asked in an interview, I've gone from knowing nothing, to knowing the step of identifying whether a command is built-in or an executable file, then to knowing about TTY, and now to understanding how commands are parsed, expanded, and sent to system calls. And every sentence in my answer might imply an interesting debug story.

Like solving a puzzle, I've gradually pieced together fragments of Bash's inner workings. While completing the full picture remains challenging, I still celebrate every time my own exploration helps snap a few pieces into place. 👍